Back يسوع في علم الأساطير المقارن Arabic Jesucristo en la mitología comparada Spanish Yesus dalam mitologi komparatif ID Gesù nella mitologia comparata Italian 비교신화학 속 예수 Korean Jesus na mitologia comparada Portuguese

| Part of a series on |

|

The study of Jesus in comparative mythology is the examination of the narratives of the life of Jesus in the Christian gospels, traditions and theology, as they relate to Christianity and other religions. Although the vast majority of New Testament scholars and historians of the ancient Near East agree that Jesus existed as a historical figure,[1][2][3][4][nb 1][nb 2][nb 3] most secular historians also agree that the gospels contain large quantities of ahistorical legendary details mixed in with historical information about Jesus's life.[10] The Synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke are heavily shaped by Jewish tradition, with the Gospel of Matthew deliberately portraying Jesus as a "new Moses".[11] Although it is highly unlikely that the authors of the Synoptic Gospels directly based any of their accounts on pagan mythology,[12] it is possible that they may have subtly shaped their accounts of Jesus's healing miracles to resemble familiar Greek stories about miracles associated with Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine.[13][14] The birth narratives of Matthew and Luke are usually seen by secular historians as legends designed to fulfill Jewish expectations about the Messiah.[15]

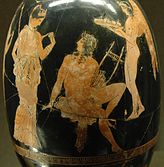

The Gospel of John bears indirect influences from Platonism, via earlier Jewish deuterocanonical texts, and may also have been influenced in less obvious ways by the cult of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, though this possibility is still disputed.[16] Later Christian traditions about Jesus were probably influenced by Greco-Roman religion and mythology. Much of Jesus's traditional iconography is apparently derived from Mediterranean deities such as Hermes, Asclepius, Serapis, and Zeus and his traditional birthdate on 25 December, which was not declared as such until the fifth century, was at one point named a holiday in honour of the Roman sun god Sol Invictus. At around the same time Christianity was expanding in the second and third centuries, the Mithraic Cult was also flourishing. Though the relationship between the two religions is still under dispute, Christian apologists at the time noted similarities between them, which some scholars have taken as evidence of borrowing, but which are more likely a result of shared cultural environment. More general comparisons have also been made between the accounts about Jesus's birth and resurrection and stories of other divine or heroic figures from across the Mediterranean world, including supposed "dying-and-rising gods" such as Tammuz, Adonis, Attis, and Osiris, although the concept of "dying-and-rising gods" itself has received scholarly criticism.

- ^ Blomberg, Craig L. (2007). The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2807-4.

- ^ Carrier, Richard Lane (2014). On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-909697-35-5.

- ^ Fox, Robin Lane (2005). The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian. Basic Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-465-02497-1.

- ^ Dickson, John (24 December 2012). "Best of 2012: The irreligious assault on the historicity of Jesus". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (22 March 2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God--Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperCollins. pp. 285. ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6.

- ^ James Douglas Grant Dunn (1 February 2010). The Historical Jesus: Five Views. SPCK Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-281-06329-1.

- ^ Michael Grant (January 2004). Jesus. Orion. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-898799-88-7.

- ^ Casey 2014, p. 243.

- ^ Richard A. Burridge; Graham Gould (2004). Jesus Now and Then. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 34. ISBN 978-0-8028-0977-3.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Ehrman 2012, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Edelstein & Edelstein 1998, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Hill 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Sanders 1993, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Salier 2004, pp. 66–69.

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).